Gerrymandering, a nefarious stratagem of electoral manipulation, is the deliberate redrawing of constituency boundaries to confer undue advantage to a particular political faction, class, or dispensation. This insidious practice, rooted in the cynical exploitation of demographic disparities, distorts democratic representation and subverts the will of the electorate.

In Kenya, gerrymandering has been weaponized by a venal political elite to perpetuate an “us versus them” narrative, strategically conjoining urban, tax-paying middle-class areas with rural hinterlands and slum enclaves. This calculated misalignment ensures that the voices of those who sustain the nation’s treasury are drowned out by the orchestrated clamor of impoverished populations, conditioned to accept privation and swayed by paltry bribes.

The result is a pernicious cycle of voter apathy, where even the most discerning citizens surrender to the fallacy that politics is the domain of peasants and slum dwellers, leaving the corrupt to plunder unimpeded.

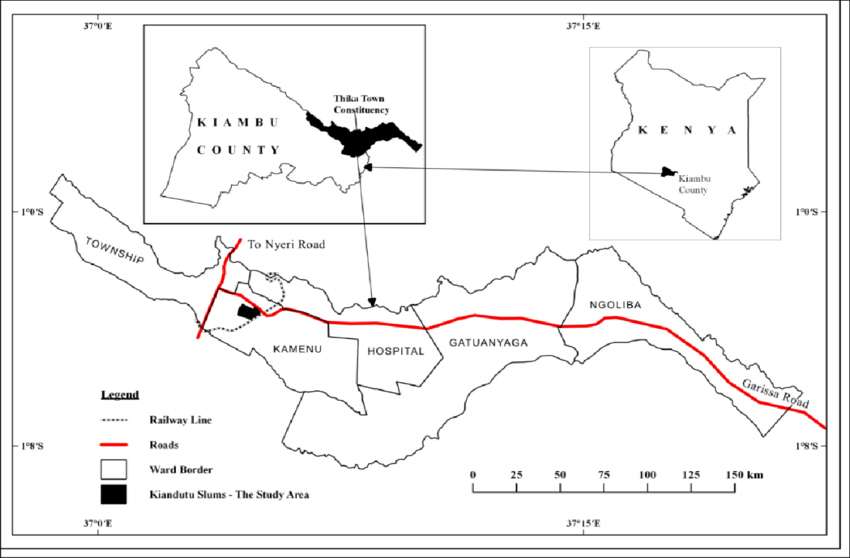

In Kenya, the middle class – those who fuel the nation’s economic engine through taxes, enterprise, and innovation – are systematically disenfranchised by electoral boundaries that dilute their influence. Urban constituencies like Thika, Nairobi’s Langata, Karen, or Westlands are grotesquely tethered to rural or slum areas such as Gatuanyaga, Kibera, or Kangemi. These regions, inhabited by populations subsisting on less than a dollar a day, are deliberately annexed to urban centers to skew electoral outcomes. Thika Constituency, for instance, is conjoined with Gatuanyaga, Magogoni, and Ngoliba – rural expanses that lie outside its administrative purview. These areas, bereft of significant tax contributions, wield disproportionate voting power, enabling politicians to prioritize their appeasement over the needs of Thika’s urban taxpayers, who demand functional drainage, garbage collection, street lighting, and potable water.

Does it make sense that a constituency called “Thika Town” has the vast majority of its land mass in rural areas?

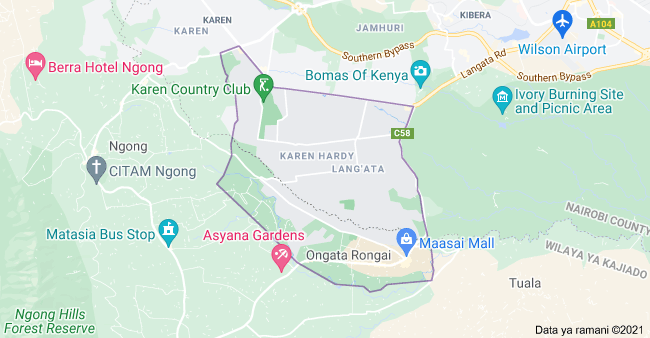

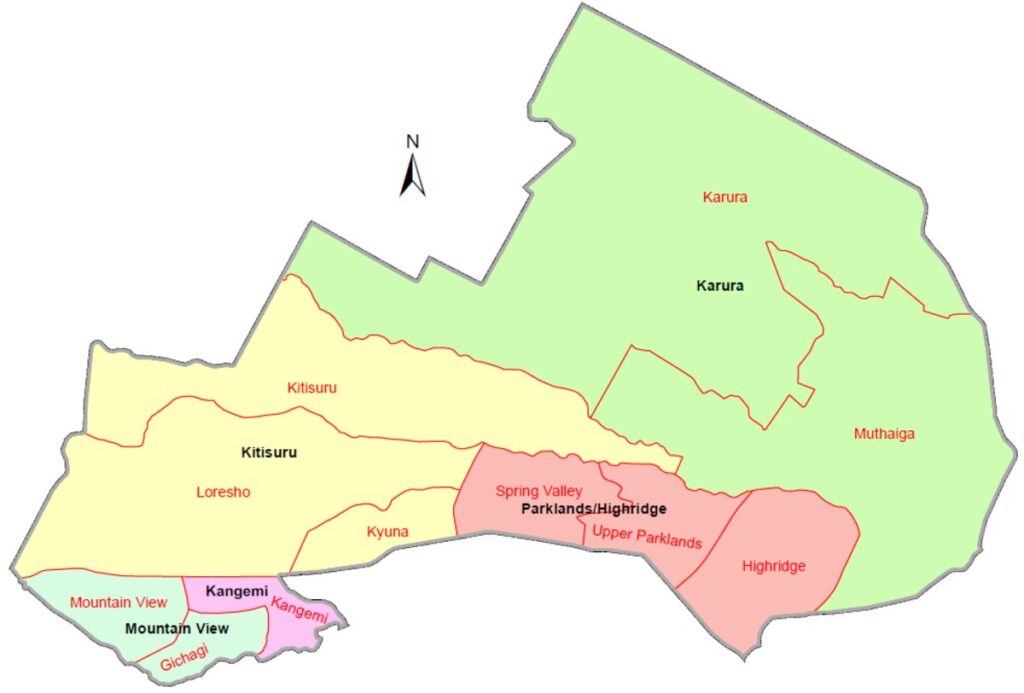

Similarly, in Nairobi, the affluent enclaves of Langata and Karen are shackled to Kibera, where votes are notoriously bartered for as little as 1,000 shillings. In Westlands, the commercial hub of casinos, hotels, and enterprises, electoral outcomes hinge on the whims of Kangemi’s slum dwellers, who are bribed with trifling sums to uphold the status quo.

This gerrymandered architecture is no accident but a premeditated gambit by political elites to entrench their dominion. By aligning urban taxpayers with populations conditioned to endure poverty, politicians ensure that the hue and cry over looted public coffers is muted. Slum dwellers and rural peasants, habituated to squalor and strife, are less likely to demand accountability for pilfered Constituency Development Fund (CDF) monies or question the absence of basic services. The middle class, meanwhile, is rendered impotent, their voting power usurped by a system that rewards lethargy over agency. The optics of peasants thronging rallies, fueled by transient handouts, create a veneer of democratic vigor, but this is a charade that culminates in voter apathy. Even Kenya’s elite, disillusioned by the spectacle of elections reduced to a transactional bazaar, retreat from civic engagement, ceding the political arena to those who peddle poverty as a weapon.

Langata Constituency comprising of left-over areas of the Kibera slums. Strategically conjoined to undermine the will of middle-income neighborhoods

The consequences are dire. Politicians, secure in their gerrymandered fiefdoms, are tone-deaf to the aspirations of the middle class, who bear the burden of inflated electricity bills, unserviced infrastructure, and neglected urban planning.

In Kibera, slum dwellers receive electricity and tarmac roads – subsidized by the very taxpayers denied similar amenities in their own neighborhoods. This inversion of justice is deliberate, designed to perpetuate a cycle where the middle class subsidizes the survival of those who undermine their electoral will. The corrupt elite, shielded by this manipulated demographic, plunder with impunity, knowing that their rural and slum constituencies are too preoccupied with survival to challenge their malfeasance.

The very affluent Westlands Constituency is dictated by the peasants and slum-dwellers of Kangemi, despite their minimal numbers and surface area

Kenya is not alone in grappling with this electoral subterfuge. Gerrymandering is a global affliction, employed by cynical political operatives to entrench power. In the United States, the practice has been honed to a fine art, with state legislatures redrawing district lines to favor incumbent parties. In North Carolina, for instance, Republican lawmakers in the 2010s crafted congressional districts that packed Democratic voters into a few urban strongholds while diluting their influence in surrounding rural areas. The resulting maps, resembling Rorschach blots more than coherent constituencies, ensured Republican supermajorities despite near-parity in statewide votes. The U.S. Supreme Court, in cases like Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), has struggled to curb this partisan chicanery, leaving states vulnerable to electoral distortions.

Similarly, in Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party has manipulated electoral boundaries to amplify rural votes, where its support is strongest, while fragmenting urban opposition strongholds in Budapest. This has entrenched Fidesz’s dominance, even as urban voters clamor for change.

In South Africa, while gerrymandering is less overt, the African National Congress has been accused of exploiting ward delineations to cluster rural voters, diluting the influence of urban middle-class constituencies in cities like Johannesburg.

These global parallels underscore a universal truth: gerrymandering is not a mere administrative quirk but a deliberate assault on democratic equity.

In Kenya, its impact is uniquely corrosive, as it weaponizes poverty to subjugate the middle class. The slum dwellers of Kibera or Kawangware, or the rural peasants of Gatuanyaga, are not the architects of this injustice but its pawns, hoodwinked by politicians who feign concern while exploiting their desperation. The middle class, by contrast, must recognize that elections are not a beauty pageant or a carnival of populist optics. They are a battleground where the future of the nation – its infrastructure, its economy, its justice – is contested. To acquiesce to voter apathy is to surrender the very agency that sustains Kenya’s vitality.

The path forward demands audacity and vigilance. The middle class must galvanize to disrupt this gerrymandered status quo. Constitutional petitions can challenge skewed boundary reviews, exposing the machinations of politicians like William Kabogo or Peter Kenneth, who sculpted constituencies to secure their voter bases in the past when they held some political capital unlike now that their future is in the dungeons.

Corrupt boomer Andrew Ligale was bribed by politicians like Raila Odinga, William Kabogo and Peter Kenneth to influence the first electoral boundaries. Today he cannot even afford healthcare.

Transparent, apolitical boundary delineation processes, insulated from political interference, are imperative. Urban areas like Westlands, Thika, or Eldoret must be delinked from slums and rural hinterlands, allowing taxpayers to elect representatives attuned to their needs – be it preserving business ecosystems in Westlands or ensuring reliable utilities in Karen. The middle class must shed its aloofness, recognizing that civic disengagement only emboldens the corrupt. By harnessing collective energy – through advocacy, litigation, and electoral participation – Kenya’s taxpayers can dismantle the gerrymandered edifice that holds them hostage.

Elections are not a spectacle for peasants and slum dwellers to barter their votes for fleeting handouts. They are a crucible where the middle class, the backbone of Kenya’s progress, must assert its rightful influence. To do otherwise is to consign the nation to the clutches of those who thrive on division, plunder, and the perpetuation of an “us versus them” dystopia.

The time to act is now, lest the gerrymandered chains of apathy and exploitation bind Kenya’s future to a fate it does not deserve.