In the annals of Kenya’s post-independence history, few events encapsulate the enduring scars of colonial subjugation and tribal manipulation as vividly as the destruction of the Kamirithu Educational and Cultural Centre in March 1982.

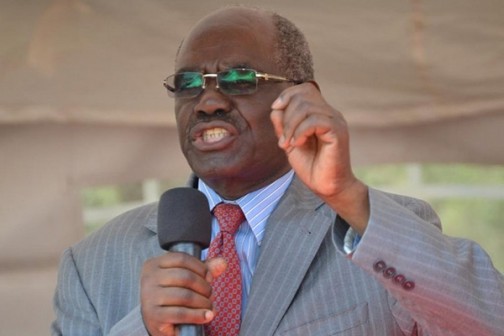

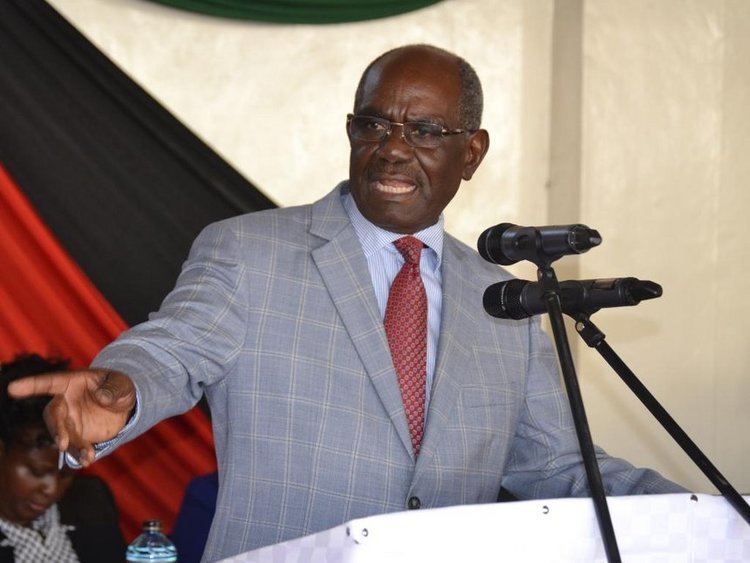

Led by Central Provincial Commissioner David Musila, this act was not merely a demolition of wooden structures but a calculated assault on the cultural and communal identity of the Kikuyu people, perpetuating a legacy of disenfranchisement that echoed the oppressive tactics of white colonial rule under the directives of President Daniel arap Moi.

This article explores Musila’s role, the broader context of tribal constructs, and how the razing of Kamirithu served as a microcosm of the cultural subjugation endured by the Kikuyu, a community long targeted for its resilience and resistance.

The Incident: A Whistle in the Dawn

On a fateful morning in March 1982, David Musila, then the Central Provincial Commissioner, arrived in Kamirithu, a small village near Nairobi, accompanied by a contingent of armed regular and administration police officers. The target was the Kamirithu Community Educational and Cultural Centre, a vibrant hub established to preserve Kikuyu heritage through education, theater, and communal gatherings.

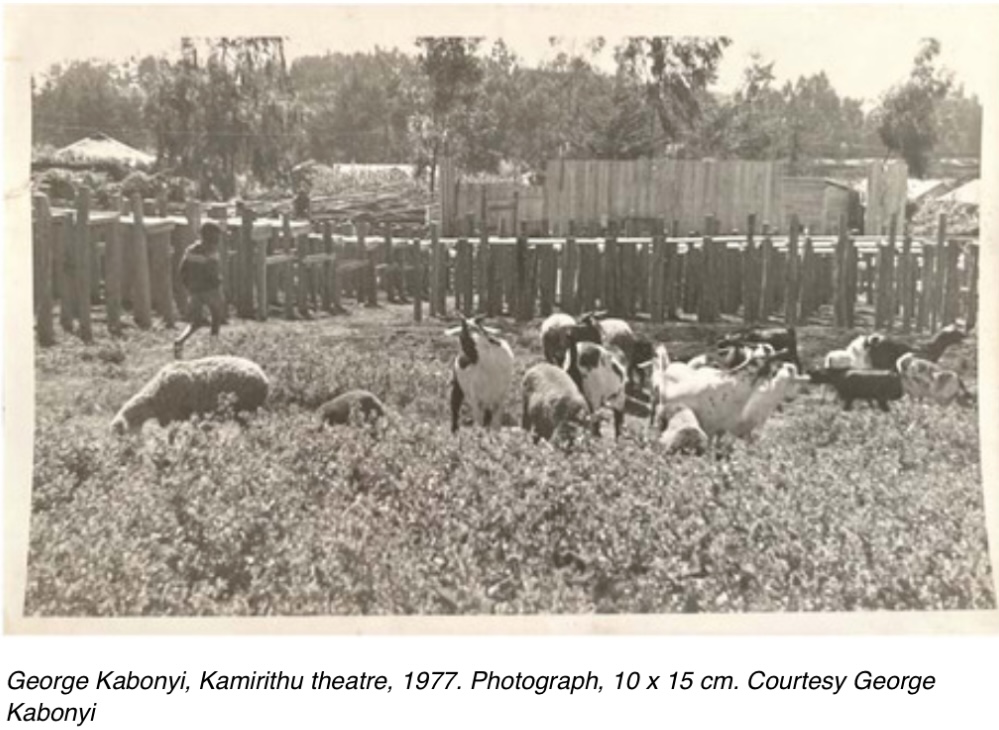

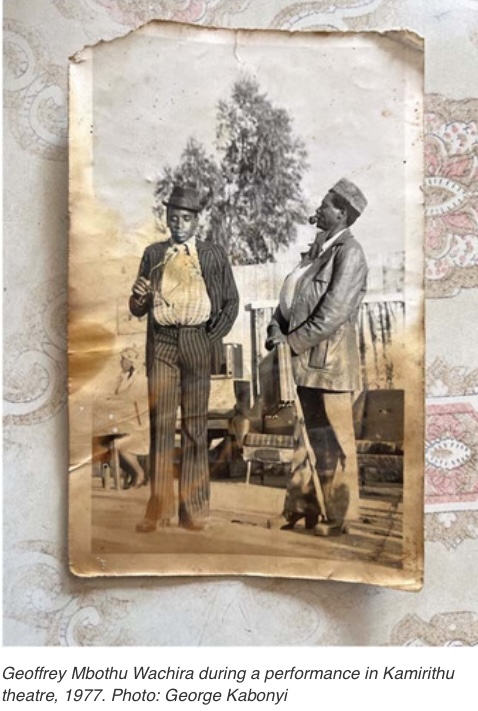

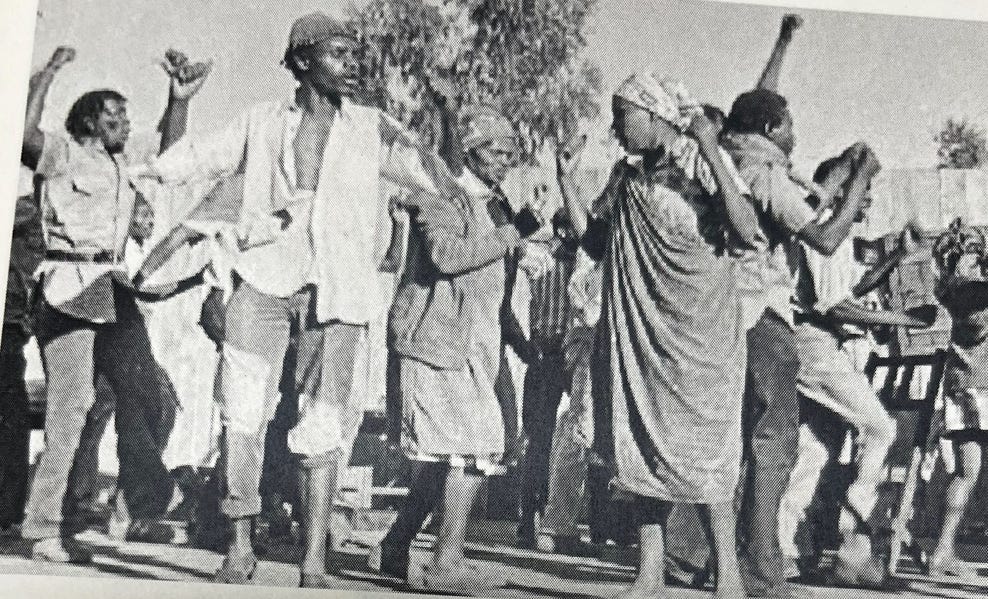

In 1976, the people of Kamirithu – local workers, peasants, and artists – came together to create more than just a performance space. They built an open-air theatre by hand, from the ground up, and used it to stage a powerful play confronting the lingering colonial injustices in post-independence Kenya. This collective act of cultural and political defiance became known as the Kamirithu Cultural Centre.

The state would later destroy the space and suppress its creators – the initiative marked one of the most radical experiments in community-led design, artistic expression and African decolonization.

Musila, wielding authority bestowed by the Moi regime, blew a whistle to summon the village residents. What followed was a chilling display of power: he ordered his men to destroy the wooden amphitheater that formed the heart of the centre, a space where the community had gathered to celebrate its identity and resist marginalization.

In a perverse twist, Musila then compelled the gathered crowd to participate in the demolition, forcing them to dismantle the remnants of their own cultural sanctuary.

This act was not an isolated incident but a deliberate move to suppress a community that had long been a thorn in the side of Moi’s government.

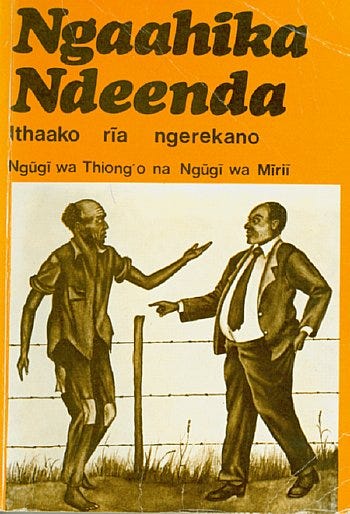

The Kamirithu Centre had gained prominence as a site of cultural resistance, notably through the staging of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), which critiqued class inequalities and colonial legacies – themes that resonated deeply with the Kikuyu, a group historically associated with the Mau Mau uprising against British rule.

The book “Ngahika Ndeenda” authored by Ngugi wa Thiongo was the script used to stage plays at the Kamirithu Cultural Center

David Musila: A Pawn in Moi’s Tribal Chessboard

David Musila, a career administrator from the Kamba community, emerged as a key enforcer of Moi’s authoritarian policies during his tenure. Moi, a Kalenjin, ascended to power in 1978 following Jomo Kenyatta’s death and quickly moved to consolidate his grip by exploiting tribal divisions.

The Kikuyu, who had dominated politically and economically under Kenyatta, were seen as a threat to Moi’s rule. Musila’s role in Central Province, a Kikuyu heartland, positioned him as an instrument of this strategy, tasked with dismantling the cultural and political strongholds of the community.

The destruction of Kamirithu is viewed as an extension of Moi’s broader campaign to weaken Kikuyu influence.

By targeting cultural shrines and communal spaces – akin to the churches, schools, and meeting places destroyed during British colonial rule – actions mirrored the tactics of cultural erasure employed by white settlers.

The entrance to Kamirithu Cultural Center in this 1977 picture

The British had sought to sever the Kikuyu from their traditions, burning shrines and banning rituals to enforce compliance.

Under Moi, this legacy was repurposed through tribal proxies like Musila, who leveraged his position to perpetuate a new form of subjugation under the guise of national unity.

Tribal Constructs and the Disenfranchisement of the Kikuyu

The Moi era was marked by a deliberate policy of tribal balancing, where non-Kikuyu administrators were often appointed to regions dominated by the Kikuyu to assert control and sow discord. Musila’s appointment to Central Province fit this pattern, reflecting Moi’s reliance on tribal constructs to maintain power.

The Kamirithu incident was not just about silencing a play or a centre; it was a symbolic attack on Kikuyu identity, a community whose cultural resilience had historically fueled resistance against oppression.

The Kikuyu, as the largest ethnic group in Kenya, had borne the brunt of colonial violence, with thousands killed or displaced during the Mau Mau insurgency of the 1950s. Their shrines – sacred spaces tied to land, ancestry, and community – were prime targets for British forces aiming to break their spirit.

The Kamirithu Cultural Center Open Air Amphitheater built by volunteers and villagers as seen in this 1977 photo

The destruction of Kamirithu, a modern incarnation of such a shrine, signaled a continuity of this strategy under Moi.

By forcing the community to destroy its own cultural heritage, Musila deepened the psychological wound, reinforcing a narrative of Kikuyu vulnerability while elevating the power of the state and its tribal allies.

Cultural Subjugation: From White Rule to Moi’s Regime

The parallels between British colonial rule and Moi’s administration are striking. During the colonial period, the British razed Kikuyu villages, confiscated land, and outlawed traditional practices to impose a foreign culture.

Moi’s government, while ostensibly independent, adopted similar methods, using state machinery to suppress dissent and erase cultural markers.

The Kamirithu Centre, with its focus on Kikuyu language and theater, represented a revival of this suppressed heritage, making it a direct challenge to Moi’s authority.

Musila’s role in this context was twofold: as an enforcer of Moi’s will and as a symbol of tribal division. His actions suggested that cultural suppression was not solely a colonial relic but a tactic refined and redeployed by post-independence leaders to maintain power.

The forced participation of the Kamirithu villagers in the destruction further echoed colonial tactics, where communities were coerced into complicity to break their collective will.

The Aftermath and Lingering Impact

The demolition of Kamirithu marked a turning point, scattering its cultural custodians and driving figures like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o into exile. Yet, it also galvanized resistance, planting seeds for future movements against tribalism and authoritarianism in Kenya.

For the Kikuyu, the loss of Kamirithu remains a poignant reminder of their vulnerability under a regime that weaponized tribal loyalty against them.

David Musila later rose to prominence as a politician, serving as a senator and cabinet minister, a testament to the complex legacy of those who enforced Moi’s policies.

His role in Kamirithu, however, stains his record, framing him as a figure who perpetuated colonial-style oppression under a new tribal guise.

Conclusion: A Call to Remember

The destruction of the Kamirithu Cultural Centre under David Musila’s command was more than a local incident; it was a microcosm of Kenya’s struggle with tribalism, cultural identity, and the lingering shadows of colonial rule.

By targeting a Kikuyu cultural shrine, Musila and Moi sought to disenfranchise a community that had long resisted subjugation, echoing the tactics of white settlers while cloaking them in the rhetoric of national unity.

As Kenya continues to grapple with its past, the story of Kamirithu serves as a stark reminder that the fight for cultural preservation and justice remains unfinished. The spirit of resistance, once embodied in that wooden amphitheater, endures – waiting to rise again.

David Musila: The Anatomy Of A Political Chameleon

David Musila’s political career is a masterclass in strategic reinvention and historical erasure.

A former Provincial Commissioner under Daniel arap Moi during the repressive one-party era, Musila was instrumental in suppressing dissent and, according to multiple accounts, oversaw the destruction of cultural and political symbols of resistance – including the dismantling of Kikuyu shrines like the Kamirithu Cultural Centre in the aftermath of the 1982 coup attempt.

THE ANATOMY OF A POLITICAL CHAMELEON: David Musila was used by Daniel Arap Moi to destroy Kikuyu cultural shrines as a measure of political suppression and subjugation tied to a colonial legacy of repression

Yet instead of being held accountable, Musila shrewdly manipulated his image, bribing journalists to sanitize his record and reframe his legacy. This enabled him to make a seamless transition into electoral politics, winning a parliamentary seat in 1997 and gradually positioning himself as a reformist voice.

Musila’s ability to pivot across regimes – aligning with KANU, LDP, ODM-K, and eventually securing high-profile roles under President Mwai Kibaki, first as Deputy Speaker and later as Assistant Minister of Defense – reveals a calculated strategy rooted not in ideology, but in self-preservation.

By masking his past through media influence and exploiting public amnesia, Musila personified a broader psychological tactic used by Kenya’s ruling elite: repackage old loyalists as agents of change.

His career reflects a system that rewards complicity with state repression and punishes historical memory, ensuring that the same faces resurface under new banners while the foundational structures of injustice remain untouched.

Kamirithu: The Forgotten Epicenter of Cultural Resistance

Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre (KCECC) stands as one of Kenya’s most powerful yet neglected symbols of cultural resistance and collective self-determination.

Established in 1976 in Kamirithu, Limuru, the open-air theatre was a radical experiment in African self-expression, reclaiming language, memory, and storytelling through performance.

The Kamirithu Cultural Center in Limuru was a beehive of activity and a source of livelihood for many

It was here that local peasants and workers crafted and staged plays in Gikuyu, the most famous being Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), a play that fearlessly exposed the lingering colonial structures of exploitation and land theft that continued long after independence.

With audiences swelling to over 10,000 people, Kamirithu was more than a theatre – it was a cultural revolution from below.

Yet this revolution was met with violent state repression. The government not only banned its performances and arrested its artists, but also physically razed the entire theatre to the ground.

That act of destruction was not incidental. It was part of a broader colonial agenda – continued by the post-colonial state – to erase any site that anchored the working class to a coherent narrative of resistance.

The ruins of Kamirithu remain untouched to this day, despite the country having had two presidents of Kikuyu descent (Mwai Kibaki and Uhuru Kenyatta) since its demolition. Their silence and inaction speak volumes.

The suppression of Kamirithu is not simply an oversight but a deliberate effort to disconnect ordinary Kenyans from their revolutionary past, ensuring that anti-colonial resistance remains fragmented, depoliticized, and stripped of its architectural and historical context.

A 3D reconstruction of the Kamirithu Cultural Center in Limuru And What The Remade Outdoor Amphitheater Would Look Like

Reviving Kamirithu would do more than preserve heritage; it would restore a suppressed memory of defiance, dignity, and community-led knowledge production. Its rehabilitation could catalyze economic revitalization through cultural tourism and community empowerment.

But more critically, it would reclaim a narrative that has long been buried under the weight of manufactured amnesia – a reminder that the true authors of history are not political elites, but the people themselves.