In Kenya, Haentel Wanjiru, widely reported as the mistress of former Kilifi County Governor and current Senate Speaker Amason Kingi, has captivated public attention with her ostentatious lifestyle. Her social media platforms are a showcase of opulence—luxurious vacations, designer outfits, high-end shoes costing Ksh 125,000, and a car allegedly gifted by Kingi. For some Kenyan women, Wanjiru’s chopper rides and haute couture symbolize empowerment and success, a rags-to-riches narrative that resonates in a society where wealth is often equated with achievement.

Yet, allegations persist that her lavish lifestyle is funded by Kingi’s misuse of Kilifi County’s public resources during his tenure as governor from 2013 to 2022. This celebration of Wanjiru’s wealth stands in stark contrast to the dire state of Kilifi County, where systemic corruption has left public services in tatters, depriving residents of basic healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

The Grim Reality in Kilifi County

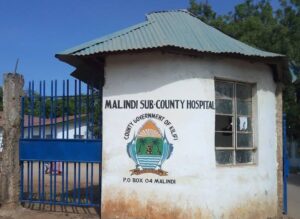

Kilifi County, one of Kenya’s 47 devolved units, grapples with poverty rates as high as 46.4% (2019 Kenya National Bureau of Statistics), with communities like Bamba facing acute deprivation. The county lacks a single Intensive Care Unit (ICU) facility, forcing residents to travel long distances for critical care. Public hospitals are underfunded, with dilapidated infrastructure and chronic shortages of medical supplies. Schools lack adequate classrooms and learning materials, while roads remain unpaved, and streetlights are scarce, hampering economic activity and safety. These challenges stem from systemic corruption, as documented in multiple Auditor-General reports, which reveal significant financial irregularities during Kingi’s administration.

Auditor-General Reports: A Trail of Financial Mismanagement

The Office of the Auditor-General, led by Nancy Gathungu, has consistently flagged Kilifi County for financial mismanagement. Below is an in-depth analysis of key reports highlighting the scale of misappropriated funds, with specific figures referenced where available:

1. 2019-2020 Financial Year (Auditor-General Report)

– The Auditor-General revealed that Kilifi County spent Sh840 million without the approval of the Controller of Budget, raising suspicions of misappropriation. This included Sh251.6 million on unapproved recurrent expenditure, Sh200 million on unauthorized development projects, and Sh389.4 million exceeding budget ceilings.

– The report also noted Sh1.2 billion in pending bills owed to suppliers and contractors, indicating funds were diverted or mismanaged, leaving critical projects stalled.

2. 2023-2024 Financial Year (Auditor-General Report)

Current Kilifi Governor Gideon Mung’aro meeting poverty-stricken constituents. He’s equally as corrupt as his predecessor Kingi

– The latest audit for the financial year ending June 30, 2024, gave Kilifi County a qualified opinion, indicating inaccuracies in financial statements. The report highlighted an unexplained variance of Sh115.1 million in transfers from the County Revenue Fund (CRF), with receipts reported at Sh13.2 billion against CRF transfers of Sh13.38 billion. This discrepancy suggests potential misreporting or diversion of funds.

– The audit also flagged irregular procurement practices and breaches of financial regulations, pointing to systemic weaknesses that facilitate corruption.

3. Historical Context: Earlier Scandals

– In 2016, the Auditor-General reported that Kilifi County could not account for **over Sh2 billion** in public funds, contributing to a broader narrative of financial plunder across Kenyan counties.

– In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Kilifi was among six coastal counties flagged for misusing Ksh 60 million meant for frontline workers, with funds spent without a budget through direct procurement.

– A 2022 investigation by the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) probed the alleged embezzlement of Ksh 1.1 billion, including payments to law firms for fictitious legal services, further illustrating the depth of rot.

– A notable fraud case involved Sh51 million siphoned through electronic banking, with initial claims of Sh1.18 billion lost.

Quantifying the Lost Opportunities

To illustrate the tangible impact of these misappropriated funds, we can estimate how many schools, hospitals, roads, and streetlights Kilifi County could have built or improved using the reported figures.

The following calculations use approximate costs based on Kenyan government estimates and industry standards for public infrastructure projects (adjusted for 2025 pricing):

1. Total Misappropriated Funds (Conservative Estimates)

– Combining key figures from Auditor-General reports:

– Sh840 million (2019-2020 unapproved expenditure)

– Sh115.1 million (2023-2024 CRF variance)

– Sh60 million (2020 COVID-19 funds misuse)

– Sh51 million (2022 banking fraud)

– Sh2 billion (2016 unaccounted funds, partial estimate to avoid overlap)

– Total: Approximately Sh3.066 billion (a conservative estimate, as other EACC probes may overlap with other figures).

2. Schools

– Cost per primary school: Constructing a standard primary school with 8 classrooms, toilets, and basic facilities costs approximately Sh20 million (based on Ministry of Education estimates for rural areas, 2025).

– Calculation: Sh3.066 billion ÷ Sh20 million = 153 primary schools.

– Impact: These schools could have served approximately 61,200 students (assuming 400 students per school), addressing classroom shortages in underserved areas like Bamba and Ganze.

3. Hospitals and Health Facilities

– Cost per Level 4 hospital: Building a Level 4 hospital with basic wards, maternity units, and diagnostic facilities costs about Sh200 million (Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council estimates, 2025).

– Calculation: Sh3.066 billion ÷ Sh200 million = 15 Level 4 hospitals.

– Cost per ICU unit: Equipping a 10-bed ICU costs approximately Sh50 million (based on Ministry of Health data for 2025).

– Calculation: Sh3.066 billion ÷ Sh50 million = 61 ICU units.

– Impact: These facilities could have provided critical care to thousands annually, addressing the absence of ICUs in Kilifi and reducing maternal and infant mortality rates.

4. Roads

– Cost per kilometer of paved road: Paving a single-lane rural road costs approximately Sh30 million per kilometer (Kenya Rural Roads Authority, 2025).

– Calculation: Sh3.066 billion ÷ Sh30 million = 102 kilometers of paved roads.

– Impact: Improved roads could connect rural communities to markets and healthcare, boosting economic activity in areas like Rabai and Kaloleni.

5. Streetlights

– Cost per solar streetlight: Installing a solar-powered streetlight costs about Sh150,000 (based on county government tenders, 2025).

– Calculation: Sh3.066 billion ÷ Sh150,000 = 20,440 streetlights.

– Impact: Streetlights would enhance safety and extend economic hours in towns like Malindi and Kilifi, particularly for women and small-scale traders.

The Hypocrisy of Admiration

The celebration of Haentel Wanjiru’s lifestyle by some Kenyan women reveals a troubling societal disconnect. Her displays of wealth – designer shoes, luxury cars, and chopper rides – are seen as aspirational, yet few question their alleged ties to Kilifi’s plundered resources. This selective admiration ignores the ethical cost: every shilling spent on Wanjiru’s lavish gifts could have funded a classroom, a hospital bed, or a kilometer of road.

For instance, the Ksh 125,000 pair of shoes could have installed 833 solar streetlights, while a Ksh 5 million car could have built a quarter of a primary school.

This idolization perpetuates a culture of impunity, where corrupt leaders face little accountability. By prioritizing materialism over collective welfare, admirers of Wanjiru’s lifestyle indirectly endorse the looting of public funds, undermining efforts to demand transparency. The Auditor-General’s reports underscore that Kilifi’s financial mismanagement is not abstract – it translates to 153 schools, 15 hospitals, 102 kilometers of roads, and 20,440 streetlights that never materialized, leaving communities in poverty and despair.

A Broader Societal Challenge

The Wanjiru-Kingi saga reflects a deeper issue in Kenya: the allure of wealth often overshadows its origins. Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Kenya 121st out of 180 countries, with a score of 32/100, indicating persistent public sector corruption. In Kilifi, public participation in budget processes is limited, with transparency scores dropping from 30% in 2020 to 9% in 2021, fostering mistrust and enabling graft. This lack of accountability allows figures like Kingi to divert funds without scrutiny, while their associates flaunt the proceeds.

For Kilifi’s residents, the consequences are stark. A mother in Bamba cannot access an ICU for her sick child, a student in Ganze studies under a tree, and a trader in Malindi navigates dark, unsafe streets. Meanwhile, Wanjiru’s Instagram posts garner likes and admiration, a painful reminder of misplaced priorities.

To break this cycle, Kenyan society must reject the glorification of ill-gotten wealth and demand accountability from leaders. Only then can counties like Kilifi realize their potential for equitable development, ensuring that public funds build schools, hospitals, and roads rather than fuel lavish lifestyles.